The Thai guesthouse that saved the remote village of Pilok in Kanchanaburi

The Thai guesthouse that saved the remote village of Pilok in Kanchanaburi

After her family’s tin mine closed and her husband passed away, Glennis Setabandhu was determined to keep the community together.

By John McMahon

25 January 2019

“The roads are not so bad today, but in the rainy season it can be quite difficult,” said Glennis Setabandhu as we waited for a battered truck to slowly make its way down the steep boulder-strewn road. “Sometimes their trucks can’t make it all the way and guests have to hike down. Once they get here, I get a cup of hot coffee and a piece of cake in them and all is well.”

At just about 5ft tall, slightly stooped with age, dressed in a long navy skirt with a flowered cardigan, 81-year-old, Australian-born Setabandhu, or Pa Glen as she’s known locally (pa being Thai for ‘auntie’), is not the type of person you’d expect to find running a guesthouse deep in the wild mountain forests around Pilok in western Thailand. But she has been for almost 30 years.

The entrance to Setabandhu’s guesthouse displays stickers, banners and T-shirts of the off-road driving clubs who have stopped here over the years. Inside, a small glass chandelier hangs over dining tables set with lace doilies. The walls are hung with old photos of Setabandhu’s family posed in their best finery, as well as snapshots of her son Narin, her grandchildren and the numerous visitors she’s welcomed over the years.

“The first time I visited the mine I was afraid… but I came to love it here”

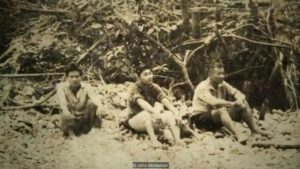

Setabandhu first came to this remote place during the cold season of 1967; her trip from Bangkok was a four-day-long adventure involving trains, boats and mules. It was here that her late husband Somsak operated a tin mine. These were ‘the good old days’ Setabandhu recalled, when more than 600 people worked together to extract the metal from the Earth’s crust.

“The first time I visited the mine I was afraid of the forest and animals, but I came to love it here,” she recalled. “This was a bustling village with families and houses all along the path. Everyone was happy.”

Setabandhu met Somsak while he was studying mining engineering at the Western Australian School of Mines in Kalgoorlie where she lived. Somsak was a badminton champion who helped coach her church team. They got married, and a few years later came to live in Thailand where he would oversee the family’s mine while she taught English at Bangkok University, travelling to the mine with Narin on school holidays.

The international tin market crash of 1985 put an end to that happy existence. Worldwide tin prices plunged, and despite his best effort, Somsak was unable to keep the mine operational. As Setabandhu tells it, her husband was heartbroken to watch the operation he had made his life’s work become defunct, which she is sure contributed to his early death by cancer in 1994.

Setabandhu made a promise to her dying husband that she would find a way to take care of his former employees and their families. “Most of the workers were from Burma [known today as Myanmar] and had no papers,” she explained. “A lot of them eventually made their way to Bangkok and got into construction work, but some didn’t want to leave the mine and the forest life. This was when I stopped teaching and came here to stay. At first I wasn’t sure what we could do here.”

One resource that could not fail was the mine’s location, set in a remote valley alongside a sparkling stream, surrounded by thick jungle and pristine forested mountains just on the border of Thailand and Myanmar. A hike along a vague trail through the scrubby jungle surrounding the guesthouse lead me to the Chet Mit waterfall, where water cascades out of the mountains so clean I didn’t think twice about drinking straight from the cold stream.

Setabandhu knew from her years of living in ever-expanding Bangkok that there were people who longed for such a place to spend relaxing weekends away from the crush of modern life.

By selling her husband’s mining equipment she raised enough money to re-purpose some of the mine’s old buildings for guests, adding conveniences like flushing toilets and gas-heated showers. She replaced the old diesel generators her husband had bought decades earlier with a small hydroelectric plant built in the stream to provide clean, silent electricity, and opened the Somsak Mine Forest Glade Home, employing the former miners who hadn’t already left for Bangkok. The guesthouse soon gained a reputation as a refuge for four-wheel drive enthusiasts and cyclists looking for some comfort in the wild.

Staying at Somsak Mine is an experience that takes you back in time and back to basics. Three decades of enduring monsoon rains and baking in the hot sun have weathered the paint so that the structures blend into the surrounding foliage. The main building, once the warehouse and company store, features a cavernous room with a soaring ceiling built of rough-hewn timber, bamboo and woven rattan, with furnishings reminiscent of a Victorian-era sitting room.

Following the old mining roads around the 200-acre concession, it’s still possible to make out the cuttings where the hills were mined through thick foliage that has reclaimed the area over the last 30 or so years. Visitors who don’t have their own transportation are ferried 5km from the town of Pilok by a local policeman who grew up at the mine; the bed of his truck is outfitted with bench seats. It’s a bumpy ride that can take up to an hour and a half depending on the last time it rained.

While the guesthouse may be remote, with no mobile service or internet access, Setabandhu makes sure that visitors are comfortable and well fed. Each evening she and her staff put together a meal that includes several Thai dishes, as well as what she describes as an ‘Aussie-style’ barbecue: grilled skewers of spice-rubbed pork, peppers and onions cooked outside on a grill. And Setabandhu’s cakes are legendary among Thailand’s off-road community. Chocolate cake, banana cake and the best carrot cake I’ve ever tasted are baked fresh each day and laid out as part of the banquet for guests to help themselves.

As proud as Setabandhu is of having hosted so many visitors over the years, her son Narin believes his mother’s real accomplishment was keeping the Somsak Mine intact and aiding the families who chose to stay on.

“I didn’t know what my mother was going to do when she moved up to the mine,” he told me over the phone from his office in Bangkok. “[But] the guesthouse allowed those who wanted to stay to make a living and created opportunities for those families that would have been all but impossible had it not come to be.”

Recently, Setabandhu told me, officials from the department of mining had visited to do some test drilling. “They said, ‘Don’t you go anywhere, Pa. The market for tin is coming back’,” she recalled. “I told them my husband was the mining engineer, but they said Somsak Mine can’t exist without me.”

“Maybe the good old days are coming back,” she added, a wistful look on her face.

Whatever the future holds, for now the doors of the Somsak Mine Forest Glade Home are open, and off-roaders, dirt bikers, trail runners and nature lovers can be assured that Setabandhu’s cakes are waiting at the end of that old rough and rocky road.

Source: http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20190124-the-thai-guesthouse-that-saved-a-village