The great rail dilemma – Laos having regrets as China’s grand Pan-Asia railway dream sours

22 July 2018

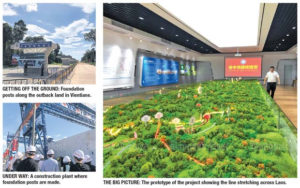

Being erected along green fields in the outback of Vientiane, where Lao farmers still busily grow rice, are a great number of meticulously situated colossal concrete columns waiting to support a high-speed railway which will connect China with Laos and change this agrarian society into a prosperous economy. Or so they say.

While construction of the project is proceeding at full steam, fears of mass Chinese immigration, as well as various other problems for the locals, have spread along the route.

SINO-LAOS RAILWAY

Of its counterparts in Southeast Asia, Lao PDR was the first to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) — China’s plan to expand regional trade and infrastructure inspired by the ancient Silk Road — in 2015, with the construction of the railway beginning in the same year. The first leg of the project is being constructed in the mountainous, mostly unpopulated terrain of Laos and is expected to finish in December 2021.

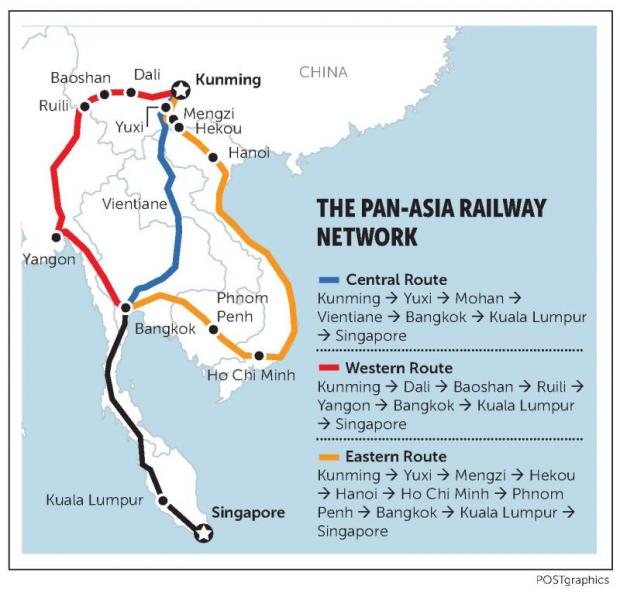

When completed, the Singapore-Kunming Rail Network, which is also known as the Pan-Asia Railway Network, will stretch across Southeast Asia, connecting eight countries, namely Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar and China.

The Sino-Laos Railway project, which is part of the larger Pan-Asia Railway, also spawned some criticism, mainly of the abrupt approval of the deal between the two governments. Many doubt whether the high-speed railway will be beneficial to the country of 6.8 million people, and since the project comes at a staggering cost of 6 billion — over one-third of Laos’ GDP — some are afraid that the burden will outweigh the benefits. A third of the cost, mostly raised through loans from China, rests on the Lao government while the rest is funded by China.

The Sino-Laos Railway is a flagship megaproject under the BRI. It is aligned with the Lao government’s vision of transforming the landlocked country into a land-linked country. The total 925.5km line will connect Mohan-Boten (on the Laos-China border) and Vientiane.

Construction on the Laos side consists of a 427km railway. Some 59% of the project is made up of bridges and tunnels. Passenger trains will run at 160km per hour and freight trains will run at 120kmh.

Construction on the Laos side consists of a 427km railway. Some 59% of the project is made up of bridges and tunnels. Passenger trains will run at 160km per hour and freight trains will run at 120kmh.

When completed, the railway will cut the time it takes to travel from Mohan-Boten to Vientiane, the capital city of Laos, from three days to less than three hours. In June, the company in charge of the construction reported that the project is 33.7% complete, which is 4% ahead of schedule.

The Chinese government and media often promote the project as a “win-win cooperation deal”, boasting the railway will provide around 5,000 jobs opportunities for local people, lower costs of production and bring wealth and development to the country. The construction company in charge also promises to build roads and improve the existing ones along the route.

However, it has been reported in Laos’ media that over 4,400 families have been removed from their homes along the proposed line. Although the families have been promised compensation by the government, none have received any money yet.

The Vientiane Times last month reported that the Minister of Public Works and Transport, Bounchanh Sinthavong, said payments would begin by the end of June. He said the loss of all property, including land, buildings, fences, crops, and trees will be compensated.

Rail compensation, which is the responsibility of the Lao government, will be paid through the National Treasury under the Ministry of Finance and is estimated to cost more than 2,492 billion kip (9.9 billion baht or US$297.73 million).

DEVELOPMENT OR DEBT

A source working for the Lao ministry of foreign affairs said the amount of debt taken on and the unbalanced agreements mean that China will ultimately be the only beneficiary of the project.

His main concern is the Lao government will not be able to solve problems caused by the project especially regarding the compensation and relocation packages promised to locals who are affected.

Above all, he said, the project will be inaccessible to the general public for whom it is likely to be far too expensive to use, adding that public transportation like buses and songtaew will remain the main form transportation.

“Laos is not ready to turn itself from landlocked into land-linked, at least not by this project,” he said.

Meanwhile, 22-year-old Thipphaphone Sihalath, a Lao living in Vientiane, said she is optimistic the Sino-Laos railway can bring about economic development.

“Sentiments on social media indicate that Laotians are happy with the project since they will be able to travel to China more easily. The northern part of the country is mountainous and roads were scarce and hard to travel along,” Ms Thipphaphone said.

“Sentiments on social media indicate that Laotians are happy with the project since they will be able to travel to China more easily. The northern part of the country is mountainous and roads were scarce and hard to travel along,” Ms Thipphaphone said.

However, she said she thinks the Chinese side will benefit more from the project, saying the aspect of the project that bothers her the most is the contract with the Chinese.

She fears that unless the government is careful, Laos will be taken advantage of, noting that in the past, when Laos failed to pay back debt owed to China, it has had to repay it with long-term land concessions and access to natural resources instead.

Ms Thipphaphone pointed out flaws in another major promise — job opportunities for locals. She said dreams of jobs were dashed when it turned out that most of those working on the project would be relocated Chinese workers, not locals.

“Most of the labourers are Chinese, and so are the head labourers. The project hires some local construction workers, but they get paid low wages,” Ms Thipphaphone said.

Meanwhile, foreigners living in Laos are also noticing the changes brought about by the flocking of Chinese migrants to the country after the project started.

“The Chinese are invading Laos. Everything is changing with the coming of the Chinese,” said a Hungarian woman who has been living in Laos for over 18 years, noting the proliferation of Chinese chain store “Miniso” which she said is affecting local competitors.

She fears that when the railway is complete, Chinese traders and migrants will flock to the country more than ever before, leaving little room for smaller local traders.

A Chinese foreign policy expert from Chulalongkorn University, Vorasakdi Mahatdhanobol, said Laos’ economic development relies heavily on China.

Mr Vorasakdi’s concern is that the country’s future rests in the hands of a political elite which is beholden to their northern benefactors.

Mr Vorasakdi said China has pushed for the rail project to happen despite being fully aware that it was unlikely to benefit Lao’s economy or people.

He is certain that people who will be using the train will mostly be Chinese, not Laotian.

For him, the railway will only further strengthen China’s grip over Laos.

IMPACT ON THAILAND

But for Thailand, the story is different.

Thailand does not rely economically on China. Moreover, without the link that will connect Nong Khai to Laos’ capital Vientiane, the grand scheme to connect China with mainland Southeast Asia will be obstructed, said Mr Vorasakdi. Talks are still ongoing between Laos, China and Thailand on whether the link between Nong Khai and the Laos capital will be built.

Mr Vorasakdi added that, however, as is the nature of a merchant country, once China had proven its technological know-how in constructing the high-speed railway, it would want to sell it to the rest of the world.

For Mr Vorasakdi, another point to consider is the main customers of the Pan-Asia railway network will be the Chinese.

He said if the Chinese come as tourists, there won’t be any problem as long as the government is ready to manage the increased volume. The problem, however, lies with the so-called “New Chinese Migrants” who, even without the high-speed rail link, have already caused Thai authorities headaches by partaking in illegal activities.

In Thailand, especially the Huai Khwang and Rama IX areas of Bangkok, new Chinatowns are developing which are home to around 3,000 recent Chinese migrants, Mr Vorasakdi said, noting the problem is not as alarming as the situation in Laos which has seen over 500,000 new Chinese immigrants since the start of the project.

“With the high-speed railway, it will be easier and cheaper for the Chinese to travel to Thailand and settle,” Mr Vorasakdi said.

“The problem lies in illegal migrants who stay without proper visas, work illegally, run businesses illegally without paying taxes or using nominees to buy land illegally.”

“In Nakorn Nayok, there is this trend of Chinese hiring local Thai girls to marry [at a cost of up to 50,000 baht] in order to use their wife’s name to buy plots of land,” he said.

However, he noted the Thai authorities are aware of the issue and working to solve it.

He added that the Chinese would not be able to do any of these things without help from the Thai side. Therefore, to solve the problem, Mr Vorasakdi said Thai officials need to have integrity and not accept bribes or any other kinds of inducement.

Source:https://www.bangkokpost.com/news/special-reports/1507722/the-great-rail-dilemma