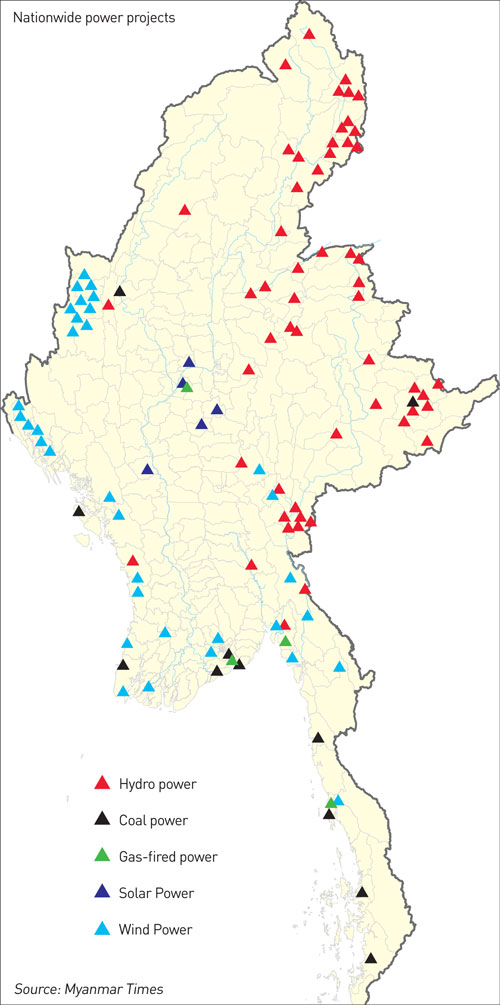

The power sector in Myanmar over the past five years has been characterised by ambitious plans and unrealised targets. While a few power projects have been completed during the outgoing government’s term, others were suspended or cancelled and dozens more remain in limbo.

Myanmar remains one of the least-powered countries in Southeast Asia. Just over 30 percent of the country’s population has access to electricity, while a total of 6.8 million households across the country still need to be electrified, according to the Ministry of Electric Power (MOEP).

Meanwhile, the country’s energy requirements are growing fast – the government’s target of nationwide power by 2030 will involve a total capacity of 24,000 megawatts of electricity, requiring vast infrastructure investment combined with smart policymaking.

Government figures suggest Myanmar has 108,000MW of hydroelectric, estimated reserves of 711 million metric tonnes of coal, 365.1 terawatt hours (TWh) per year of wind power and 51,973TWh per year of solar power. It also has 459 million barrels per day of proven oil reserves and 11.8 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves.

For now, however, the country’s huge primary resources for electricity generation remain largely locked up. While the outgoing government has successfully tendered a number of oil and gas blocks, attempts to develop other power sources, particularly hydropower, have struggled to get off the ground.

As a result of the lack of comprehensive laws, policies, and environmental and social protection standards, many potential power projects have become controversial. The first controversy concerns the price of electricity – K35 per KWh for household use and K75 per KWh for industry users.

This is lower than the average electricity production cost of K93.67 per KWh according to the MOEP, and is costing the government billions of kyat a year in subsidies. An attempt to raise electricity prices to allow for a return on commercial investments was blocked by the Union parliament.

The second controversy surrounds the implementation of large hydropower and coal-fired power projects. Presented with inadequate information about the social and environmental impacts of such projects and fearing the worst, local communities and civil society groups have generally opposed them through protests.

Such resistance led to the suspension of the controversial US$3.6 billion Chinese-backed Myitsone hydropower dam, which would have generated 6000MW of electricity. The government has also signed memorandums of understanding for at least 11 coal-fired power plants across the country, but none has been able to move forward due to widespread opposition.

“We have tried to explain our project to the public but they are ready to oppose it every time,” said a consultant who is working for a local company on a coal-fired power project. “We don’t get help from the government and people don’t listen. They don’t believe in government policy or what we are doing.”

Last year the government cancelled a 279MW coal-fired power plant in Yangon’s Htantabin township. All the other coal projects across the country, ranging from 200MW to more than 600MW of installed capacity, are on hold.

Something has to give in order for the government to achieve its target of 100pc electrification by 2030. Current electricity consumption is 2700MW, much lower than the 27,000MW used in neighbouring Thailand. Myanmar’s Energy Master Plan targets installed capacity of 4531MW in 2020, 8121MW in 2025 and 14,524MW by 2030, which will require investment of between US$30 billion and $40 billion over 15 to 20 years. Yet targets are being missed, said U Htain Lwin, permanent secretary at the MOEP.

“We didn’t meet the target in the last five years because we failed to implement large-scale hydropower projects due to public opposition. The same is true of coal-fired plants as well,” he said. “It will be very difficult to meet the target if we cannot continue these large-scale projects in the next five years. Our electricity generation may stop but demand will not.”

A slow start for hydro and coal

Just 3000MW of an estimated 100,000MW of hydropower resources have been harnessed. Nine dams generating a total of 800MW have been completed in the past five years, but many others are on hold due to environmental and social concern. Most notable among the suspensions is the giant Myitsone dam in Kachin State.

“The impact of suspending Myitsone was huge,” said an official at the electric power ministry, noting that the Chinese investor was not impressed. “We have invited other international companies [to develop hydropower] but only a few have invested. Actually only China can complete such large-scale projects,” he said.

“In terms of investment, technology and logistics, no other international companies can compete with China, not only in Myanmar but globally.” In Myanmar a total of 52 hydropower projects are under development – more than 30 of which are run by at least 12 Chinese companies, the official said.

Coal power in Myanmar is even less developed, though is expected to make up 20pc of total power by 2030 under the Energy Master Plan.

The country has just one coal-fired power plant, a Chinese-backed 225MW project, which has been suspended due to poor regulation. The government has also signed at least 11 contracts for new coal plants with companies from China, Thailand and Japan.

Yet the use of coal-power is fervently opposed by many in Myanmar, with local and international experts vociferously arguing that there is no place for the pollutant in the country’s energy mix.

Co-founder of Ecodev U Win Myo Thu said, “Today, coal power is a great concern internationally as the world is looking to reduce carbon emissions due to climate change.”

Others disagree – speaking at a Yangon summit hosted by The Economist last year, Asian Development Bank vice president Stephen Groff said there is a place for coal generation in Asia’s future energy supply, as long as its negative impacts are minimised.

A future in gas and renewables

Gas-fired power projects are the most favourable option due to their clean electricity output, but they are also the most expensive. The government has tried to meet electricity generation targets with gas over the past five years, but most of the plants are engine-based, and short-term solutions. Gas power is limited not only by cost but by a lack of supply.

Myanmar’s four offshore gas fields are locked into long-term contracts with Thailand and China, and recent gas discoveries have not yet been confirmed as commercially viable. Even if they are, commercial production will take at least 10 years.

“We are exporting around 1.7 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas and delivering around 400 million cubic feet per day of gas for domestic use,” said U Myo Myint Oo, managing director of Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise, last year. “We have to deliver gas according to demand and we have to abide by the contracts. That’s the situation.”

The government is implementing three gas-fired power plants at Thilawa in Yangon, Myingyan in Mandalay and Thaton in Mon State, with a total combined capacity of 380MW. It has also signed a memorandum of understanding for a gas-fired power plant in Thanlyin in Yangon. A consortium led by Japan’s Marubeni Corporation is conducting a feasibility study and plans to invest $1 billion into the plant, which will have a capacity of 400MW.

A final option is to develop renewable energy sources. At present, there are no wind or solar power projects connected to the national grid, though the government is aiming for 9pc renewable energy by 2030. A number of solar and wind projects have been signed and are likely to come online in the next few years. US-based private equity fund ACO Investment Group and Thailand’s Green Earth Power Company are building solar projects in Mandalay and Magwe, to generate more than 500MW of electricity. More local and international companies are doing feasibility studies across Rakhine, Chin, Ayeyarwady, Yangon, Shan, Kayah, Kayin, Mon, and Tanintharyi. The MOEP estimates that wind power projects could create around 5000MW of electricity.

Facing the challenges ahead

Since political and economic reforms began in 2011, the government has made power generation a priority and has welcomed foreign investment to help build capacity. Since then, FDI into power has flooded in, representing 20pc of total foreign investment over the past five years. Investment from China has dominated, followed by ventures from Singapore, Thailand, the US, the UK, Japan, Norway and other Asian countries.

It is likely that the new government will continue this open-door policy toward foreign investment into the power sector, yet it will need to navigate a number of unavoidable challenges. The National League for Democracy-led government, which was sworn in earlier this week, has elected to form an energy superministry, combining the Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Electric Power into the Ministry of Electricity. It will be overseen by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who has taken on a total of four ministerial positions.

While she may lack technical expertise, this will give her a significant role in grappling with the problem of power generation and will put her on the front line of decisions about existing divisive projects such as

Myitsone, as well as future tenders related to the sector.

The first area of focus should be to publicise laws, rules and regulations relating to the sector, as well as formulating new policies, experts said, adding that controversial issues surrounding the large hydro and coal projects will not go away without proper policy management.

Other major reforms could include liberalising electricity prices, implementing clear standards for divisive projects, focusing more on renewable solutions, creating a profitable climate for investors and developing human resources to help strengthen the government’s regulatory capacity.

The new administration, led by the NLD, will need to find ways of making power projects into success stories, said an official from the MOEP. Electrification is not only about generation but about transmission and distribution, he said.

“The most important thing, above all, is policy. If we have clear guidelines we can move ahead with speed. I think the combination of two ministries is a good sign, because we have no cooperation at the moment.”

The outgoing government spent more than $2.7 billion on the power sector in the past five years across generation, transmission and distribution, according to the MOEP. It also borrowed $1.69 billion from international institutions under various loan programs. Of this, only $103.9 million has been spent in the past five years, said U Khin Maung Soe, outgoing Union minister for electric power, on March 20.

“The other $1.5 billion is to be spent by the next government,” he said.

Source: http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/business/19790-power-sector-lofty-goals-missed-targets.html