The New Law Courts building under renovation pictured from Strand Road in Yangon (Courtesy of Heritage Hotel Kempinski Yangon)

From law courts to luxury in Yangon; the Heritage Hotel Kempinski Yangon

Downtown’s largest restoration project to open as 5-star hotel

YANGON — Downtown Yangon’s largest restoration project to date will open its doors this spring, no longer as a somber law and justice institution, but as a luxurious five-star hotel.

The transformation of Myanmar’s colonial-era New Law Courts into the elegant Heritage Hotel Kempinski Yangon will not only help meet demand for upmarket hotel rooms and function spaces in the city. It will also act as a spur to other restoration projects that will eventually dispel the ghost-town pall that has hung over the colonial heart of Yangon since the Myanmar government decamped wholesale to the stark new capital Naypyitaw in 2005-06.

Already underway is the conversion of the nearby Burma Railways building to a Peninsula hotel, and restoration has recently started on the old Tourist Burma building, on Sule Pagoda Road, which will also become a hotel.

The New Law Courts transformation signposts the way in which empty and derelict structures can take on a new lease of life, and in the case of Yangon not only preserve a unique collection of colonial architecture but also enrich the nation’s culture and its coffers.

The massive restoration work is being undertaken by a joint venture between Thailand-based renovation and decor specialist Kanok Furniture & Decoration, and Myanmar’s Jewelry Luck Group.

Thailand’s Siam Commercial Bank has provided $71 million of funding for the restoration. SCB’s largest shareholder is Thailand’s Crown Property Bureau, which administers the property of the Royal House of Thailand, and which also has a stake in Switzerland-based Kempinski.

Kempinski, which traces its origins back to Germany in 1897, and can claim to be Europe’s oldest-established luxury hotel group, has a long history of managing heritage hotels.

Thailand’s Crown Property Bureau was a majority shareholder in Kempinski between 2004 and 2017, allowing the company to embark on a global expansion that included the opening of the new-build Kempinski Nay Pyi Taw, in Myanmar’s capital. In 2017 the Kingdom of Bahrain, which had previously been a minority shareholder in Kempinski, became the majority shareholder.

Jewelry Luck Group, usually known as JL Group, was founded in Myanmar in 1995 and has extensive interests in timber manufacturing, trading and hotel operations. Kanok was founded as a furniture maker in Thailand in 1971, and has since expanded into restoration, interior design and construction, with a track record of more than 200 hotel and serviced apartment projects. The joint venture they have formed is named Prime Residence and Heritage Hotel Kempinski Yangon.

Kempinski has been advising on developing the New Law Courts — which stand on the site of the earlier Court House — to international hotel standards.

The building had been shuttered and slated for redevelopment since 2012. Permission to undertake the work was granted in 2014, but the early days were fraught with controversy, mainly from lawyers who objected to the loss of a property with a long legal history. Once that dispute was resolved, in 2016, restoration began.

“It has been an incredible saga,” said Supalak Foong, managing director of Prime Residence and a director of Kanok. During a recent tour of the site, the hyper-energetic Supalak explained that the project was being undertaken in cooperation with Yangon Heritage Trust, the country’s leading architectural conservation group, in order to ensure authenticity to the building’s original concept.

“We knew there were no shortcuts,” she said. “But the building was in relatively good condition.”

A Scottish architect, Thomas Oliphant Foster, designed the building, which was constructed from 1927 to 1931. Foster used a dramatic row of Ionic columns, three stories high, which he placed above a single-story colonnade, forming a massive presence on Strand Road, which runs along the Yangon riverfront.

At the time, steel-frame construction was changing the form of Yangon’s colonial buildings, allowing architects to design larger structures with fewer internal support columns. Foster designed a massive 3,000-ton frame for the New Law Courts which was fabricated in England by Dorman Long, a company that also built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and then shipped out to Yangon.

As she led the way through what used to be an open courtyard on the ground floor, Supalak voiced particular pride about the installation of roof structure that had been prefabricated in Thailand. The newly enclosed space will be the hotel ballroom, able to hold 1,000 guests.

The building was one of the first in Yangon to be equipped with an elevator, and the original bronze doors have been retained, along with other bronze fixtures and the original teak handrails that help to impart a sense of old-world dignity.

One of the highlights of the restoration work, according to Supalak, was the discovery in one of the upstairs rooms of a false ceiling that hid splendid decoration — probably due to a decision by bureaucrats to help reduce the amount of space requiring cooling by electric fans. When the ceiling was removed, handsome filigree moldings were discovered. The space will now be used as one of the main function rooms, Supalak said.

Elsewhere on the upper levels, the 90-year-old wooden shutters are still in sound shape and are being retained. One feature that will not figure in the finished hotel is the old court cells, just below the roof, which came in useful when the Japanese Kempeitai military police occupied the building in World War II.

The rooftop itself is being turned into a large open space with a garden, a bar and pool, and a view of the Yangon River.

Of the 3,000-strong workforce at the peak period of the restoration project, 200 workers were Thai. Now, with building work winding down, the hotel, which is directly opposite the new riverside cruise terminal, is readying its 350 staff to breathe life into the structure.

The general manager, Ed Brea, said staff will start on-the-job and classroom training from April. The vast majority of staff are local, said Brea, with about half being “repats” — Myanmar personnel with years of overseas experience. Only around a dozen are expats, mainly supporting the food and beverage operation.

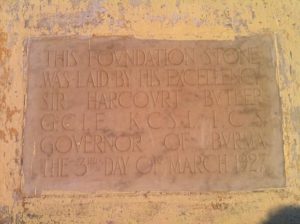

The building’s original foundation stone, dated 1927 (Courtesy of Heritage Hotel Kempinski Yangon)

The grand opening of the hotel, at which it becomes fully functional, will be held in the fourth quarter of this year.

Supalak is confident that the Kempinski will rejuvenate Bank Street, the short, straight thoroughfare that cuts through from Strand Road to Sule Pagoda Road. Half of Bank Street’s south side is occupied by the hotel, and the recently opened Yangon Stock Exchange, in another colonial-era building, stands at the western entrance. But the rest of the street is pot-holed and semi-derelict, characterized by the squatter-haunted Balthazar building and the crumbling pepper-pot towers of the old Accountant General’s Office.

The Prime Residence joint venture has submitted a Bank Street master plan to the Yangon City Development Committee that would include traffic management and parking systems, road resurfacing, pedestrian zones, and vendor locations.

“This would be a beautiful space for local office workers and tourists to wander, sit beneath the trees, and enjoy coffee at pavement cafes,” Supalak said.

Source: https://asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Life/From-law-courts-to-luxury-in-Yangon