Editorial Opinion

Justice always comes late. But when it came last Thursday — in one of the Klong Dan corruption cases — it was indeed welcome because, at least, it has proven that corruption does not pay.

Three former officials of the Pollution Control Department (PCD), namely Pakit Kiravanich, the former director-general of the department, his deputy Sirithan Pairoj-Boriboon, and Yuwaree Inna, an official in charge of the Klong Dan waste water treatment project, were sentenced to 20 years imprisonment by the Criminal Court on Thursday.

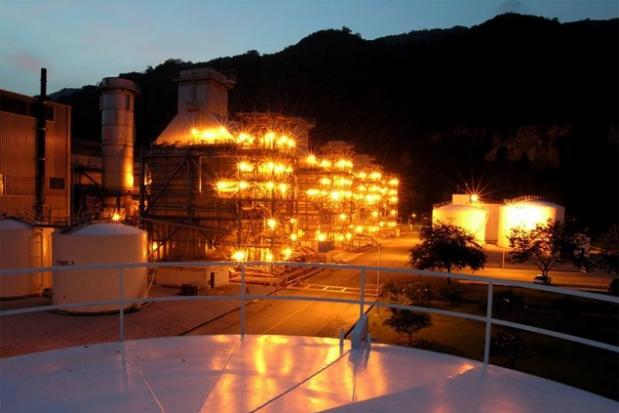

The court found the trio, who were responsible for setting the specifications for the project and for screening the qualifications of the bidders, guilty of abusing their authority by helping the NVPSKG consortium win the contract to build the 23.7-billion baht facility in Klong Dan, Samut Prakan in a way beneficial to the private sector but damaging to the state.

The trio were later released on two million baht bail each.

A little background about the consortium and the project, especially the aspect about the project’s land will help readers understand the corruption conspiracy which has earned the project the infamous reputation of being the “mother of all corruption” cases.

NVPSKG stands for the following companies: N for Northwest Water National, which later pulled out of the project; V for the Vichitphan Construction Company, owned by the Chavananond family; P stands for the Prayoonviskarnchang Company, whose founder is Vis Lipatapallop, the father of Chart Pattana Party leader Suwat Lipatapallop; S stands for the Seesaeng Karn Yotha Company, whose founder is Banharn Silpa-archa but which is now owned by the Wongjirotekul family; K stands for the Krungthon Engineering Company, which is an affiliate of Vichitphan Construction; and G stands for group.

Minus Northwest Water National, which pulled out, you can see the political connections of these companies.

On top of that, there are three other key players in the project — the Muangrae Lan Thong Company, Klong Dan Marine & Fishery Company and the Palm Beach Development Company — which were involved in acquiring the 1,900 rai which was eventually sold to the PCD as the location for the plant.

The land issue became the focus of a corruption probe against then deputy interior minister Vatana Asahame who was eventually prosecuted and sentenced to 10 years in jail by the Supreme Court’s Criminal Division for Political Office-Holders. Vatana fled the country before the reading of the court’s verdict, as if he knew his fate in advance.

The truth is that Vatana, through Muangrae Lan Thong, abused his authority to buy land from villagers at about 20,000 baht per rai and encroach on swamp land to form one big tract of 1,900 rai. The land was then sold to Palm Beach Development and then to Klong Dan Marine & Fishery before it was sold to the PCD at about 260,000 baht per rai.

How was swamp land able to be issued with title deeds? The answer is that some land officials in Samut Prakan had their arms twisted to help out in exchange for some inducement, and that those responsible were later charged in court with malfeasance in office.

The original plan for the water treatment project called for two separate facilities — one on the western side of the Chao Phraya River to receive industrial effluent from Phra Samut Chedi and Phra Pradaeng districts and Sooksawat Road (to be treated at tambon Bang Pla Kod in Phra Samut Chedi district) and the other on the eastern side of the river to receive waste water from Muang, Phra Pradaeng, Bang Pu and north of Bang Phli district (to be treated at the facility in Bang Pu Mai).

In the middle of the bidding procedures, the project specifications were abruptly changed by the PCD. Instead of two separate treatment facilities, the department demanded one single site at Klong Dan which is about 20 kilometres away.

By coincidence, there was the ideal plot there for it, and it was being quietly acquired by Vatana and his associates.

Originally, there were 13 bidders, but only four passed the department’s pre-qualification assessments. Only two submitted sealed bids: NVPSKG and Marubeni. Marubeni finally pulled out because it could not find the land needed for the project, leaving NVPSKG as the sole bidder and therefore the winner.

The project is a turn-key project which means the successful bidder does everything itself, including land acquisition.

After completion of the project, the consortium hands over the keys of the facility to the government.

Because of the change to the specifications, the cost ballooned from about 13 billion baht to 23.7 billion baht as an underground pipe line system was needed to carry waste to the plant.

The ridiculous aspect of the project was that the cost of the pipeline system was higher than that of the plant itself.

The point in explaining the background of the project, the changes to the specifications and all those “coincidences” is to inform readers about why some people are fiercely demanding the government withhold paying the so-called “stupidity fee” of about 9.6 billion baht (in construction costs) to the NVPSKG consortium as ruled by the Supreme Administrative Court.

These people include residents of Klong Dan and former anti-corruption commissioner Vicha Mahakyun. All want a clearer picture about this consortium — whether it knew anything about the fishy activities that went on during the bidding, or about how the land was acquired — after the rulings of other courts such as the one by the Criminal Court last Thursday.

Sadly, Deputy Prime Minister Wissanu Krea-ngam thinks otherwise. He said the government is duty-bound to follow the Supreme Administrative Court’s ruling.

The construction fee owed to the builder, he said, is a separate issue from the corruption issue of which several cases are still pending in court.

Veera Prateepchaikul is a former editor, Bangkok Post.

Source: http://m.bangkokpost.com/opinion/800692