TAMAKI KYOZUKA, Nikkei staff writer

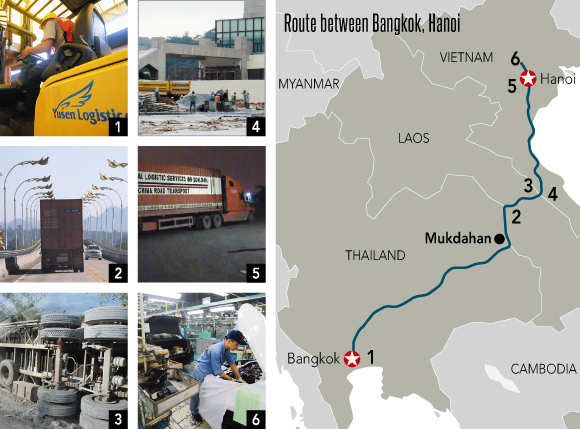

There’s nothing like a road trip to get a sense of a place. So to see for ourselves how Southeast Asia is preparing for the launch of the ASEAN Economic Community, we hit the highway and followed Toyota Motor’s ground supply chain across Indochina.

Members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have already eliminated tariffs on 96% of goods traded within the bloc. The next step is to bring down, or at least standardize, nontariff barriers such as customs clearance procedures. This aspect of the AEC promises to make life a lot easier for logistics companies and multinational manufacturers with local production bases, like Toyota.

But as we soon found, there is still a long way to go.

A CORRIDOR TO AVOID It’s 1 p.m. on a Friday in late November, and a truck is pulling out of Yusen Logistics Thailand’s warehouse near Bangkok. It is loaded with batteries for Toyota, as well as goods bound for other customers.

Each month, the Japanese automaker procures 1,000 batteries from a manufacturer in Thailand and has them trucked about 1,500km to its auto plant in Hanoi. The route runs across Laos.

Driving the truck this time is a Thai couple — Manit Onsuwan, 39, and his 30-year-old wife, Penchan Khantongdee.

Thai truck drivers of Yusen Logistics hand over their job to their Vietnamese counterparts at the border between Thailand and Vietnam (Photo by Keiichiro Asahara)

The journey starts on a paved highway with three lanes heading each way. Eventually, the road narrows to two lanes on each side, then just one. The truck runs at a cruising speed of 60kph to 70kph but occasionally slows to less than 50kph on the one-lane stretches.

Thailand’s arterial roads are flanked by modern gas stations with convenience stores and clean washrooms. We take a few breaks at these rest stops and, 12 hours after our departure, arrive in the Thai town of Mukdahan. At a gas station there, Penchan eats a cup of instant noodles she bought. “My husband will take the wheel now,” she says.

Situated next to the Mekong River, Mukdahan is a pivot point along the East-West Economic Corridor, which runs through Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. Yet rather than make the crossing there, we drive another 100km north in Thailand to cross from Nakhon Phanom.

Hirofumi Sadakata of Yusen Logistics’ Mekong logistics division, who is along for the ride, says the East-West corridor is unusable due to the poor condition of the roads in Laos. Governments and the Asian Development Bank aim to make the corridor the focus of AEC logistics, but those roads will have to be improved first.

We make it to Nakhon Phanom at 3:20 a.m., Saturday morning. The immigration and customs building is lit up behind a closed gate.

“INDISPENSABLE” HELP At 9 a.m. we meet up with a shipping agent — a representative of the logistics company who handles the clearance process. The agent exchanges friendly words with a local official, get the clearance done in 10 minutes, and soon we are on our way again.

But why does an agent need to be there in the first place? The company uses not one but four — two on each side of the border. “Right now, they’re indispensable,” Sadakata says.

The 10 ASEAN member states have yet to standardize customs clearance documents and procedures, requiring exporters and importers to prepare documents for each government. Since truck drivers cannot be expected to handle all this paperwork, logistics companies have to station agents at the borders.

Thai customs officials know they need to iron things out in preparation for economic integration. “We hold sessions in our office to study how to streamline operations, as the transport of goods will increase after the start of the AEC,” said Tatree Vichitagul, a Thai custom official at Nakhon Phanom.

ROUGH PATCH In Thakhek, on the Laotian side of the border, another shipping agency carries out the customs procedures. “We will return to Bangkok,” Manit says, moving the containers onto a truck driven by a Vietnamese driver.

Trucks and drivers with Thai licenses are allowed to operate only within Thailand. An AEC agreement on cross-border transport of goods has yet to be put into practice, due to a lack of necessary legislation in individual countries. Laos and Vietnam, however, struck a deal of their own to accept each other’s trucks and drivers. Yusen takes advantage of this and uses Vietnamese drivers in both countries.

Nguyen Xuan Ha, 36, who took over the containers from Manit, leaves Thakhek at 11 a.m. The Laotian roads, with one lane going each way, are rough. After about four hours, we are around 10km from Na Phao on the border with Vietnam, and things get even bumpier.

Ha maneuvers slowly and carefully on the bone-jarring road. The pavement has worn away due to the passage of heavy-duty trucks. Big trucks that overturned lie abandoned.

After another hour, at about 4 p.m., we make it to the border.

The procedures for leaving Laos are simple. A small team of officials handles the process out of a modest immigration control building. The atmosphere changes when we get to Cha Lo, a border area in Vietnam. A large customs and immigration building is under construction, reflecting the Vietnamese government’s expectations of an increase in cross-border logistics activity.

Numerous uniformed officials keep a lookout for illegal goods and unauthorized travelers. The customs and immigration procedures take time here, almost an hour, despite the presence of a shipping agent. We are finally ready to go at 5 p.m. — 28 hours since we left Bangkok. Ha says he is ready for the 11-hour drive to Hanoi.

FINAL STRETCH Vietnam’s well-paved roads offer relief for those weary bones. After descending on a mountain road for more than an hour, with some 400km still to go. We take an arterial road with, along most sections, two lanes on each side. But it is slow going in urban areas, where the speed limit is lower and parked cars often give drivers only one lane to work with.

Unlike in Thailand, there are no modern gas stations along the way. We keep moving, stopping only for one meal break and a couple of brief toilet breaks. At about 4 a.m. on Sunday morning, we complete our 39-hour journey at a parking lot of a bond warehouse in Hanoi.

The ex-bond procedure begins at 9 a.m. on Monday. An official from Vietnam Maritime Development, a state-owned company that manages the warehouse, oversees the entire procedure.

Currently, goods trucked from Thailand account for only 15% of what passes through the warehouse. But a manager at Vietnam Maritime Development expects that ratio to increase.

Yusen’s Sadakata says, “We’re getting more inquiries, as many companies are seeking business opportunities in the Mekong region.”

He concedes that many of those inquiries fail to turn into contracts, due to costs. Land transport from Bangkok to Hanoi takes two days, much shorter than 10 days that takes to ship goods by sea. But it costs three to four times more. Smoother customs procedures and better infrastructure would further cut the trucking time, making it a more attractive option. And higher demand would allow companies like Yusen to pack more goods onto each round-trip truck, Sadakata says, and lower the costs.

The batteries we brought from Thailand are taken to Toyota’s Vietnamese plant, destined for small vehicles such as the Vios. The plant is running at full capacity thanks to strong sales in the country. Our 1,500km journey ends with a worker fitting one of the batteries into a car, which rolls off the assembly line with a honk.

Source: http://asia.nikkei.com/magazine/20151217-ASEAN-ECONOMIC-COMMUNITY-REALITY-CHECK/On-the-Cover/Bumps-and-bottlenecks-on-the-road-from-Thailand-to-Vietnam?page=2